Horse in Motion

| Site: | MightyLMS - Quản lý giáo dục |

| Course: | Applied English for Science and Technology |

| Book: | Horse in Motion |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 23 January 2026, 5:06 PM |

Description

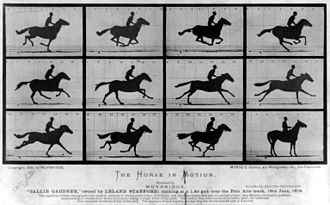

It may come as a surprise in the twenty-first century to discover that, in the 1880s, details of how objects move were unknown. The human eye, unaided, cannot resolve the details of fast motion. Eadweard Muybridge and his experiments with motion photography, such as this series of pictures of a horse's gait, helped solve this mystery.

From http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/windows/southeast/eadweard_muybridge.html - edited

Eadweard Muybridge

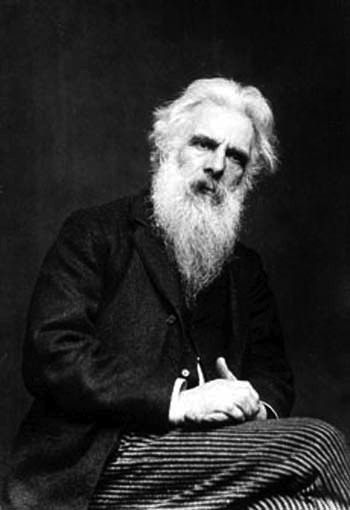

Eadweard Muybridge (9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection.

Eadweard Muybridge (9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection.

In the 1880s, Muybridge entered a very productive period at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, producing over 100,000 images of animals and humans in motion, capturing what the human eye could not distinguish as separate movements. He spent much of his later years giving public lectures and demonstrations of his photography and early motion picture sequences, travelling back to England and Europe to publicise his work. He also edited and published compilations of his work, which greatly influenced visual artists and the developing fields of scientific and industrial photography.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eadweard_Muybridge - shortened

A galloping horse

His most famous work began in 1872, when he was hired by Leland Stanford (later the founder of Stanford University) to photograph horses. Stanford reputedly had made a bet that for a moment, all four of a racehorse's hooves are off the ground simultaneously, and he hired Muybridge to take the pictures to prove him right. This was difficult to do with the cameras of the time, and the initial experiments produced only indistinct images. The photographer then became distracted when he discovered that his young wife had taken a lover and may even have had their child by him. Muybridge tracked down the lover and shot and killed him. When Muybridge stood trial, he did not deny the killing, but he was nonetheless acquitted.

Muybridge left San Francisco and spent two years in Guatemala. On his return, Muybridge resumed his photography of horses in motion, this time far more successfully. … The results settled the debate once and for all: all four hooves do leave the ground at once, as the top middle image in this sequence demonstrates.

Muybridge left San Francisco and spent two years in Guatemala. On his return, Muybridge resumed his photography of horses in motion, this time far more successfully. … The results settled the debate once and for all: all four hooves do leave the ground at once, as the top middle image in this sequence demonstrates.

From http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/permanent/windows/southeast/eadweard_muybridge.html - edited and shortened

Test your mobile phone

TASK 1: Use your mobile phone and take 12 consecutive photos of a classmate as s/he walks leisurely across the classroom. Do not use an app like Stop Motion Recorder or PicPac; use your own skill! Then, place these photos one after the other to see if you can manage to create a short motion picture of "A Student in Motion".

TASK 2: Work as a group. For example, six or more students stand shoulder to shoulder and you walk leisurely before them. Depending on the number of photo-shooters, each person can take maximum two photos (without using an app). Before the photo-shooting session, decide how you will trigger the event and how each member will know when they should start and finish taking their photos. The end result should be the same as in Task 1. Tell other groups how you accomplished the task.

TASK 2: Work as a group. For example, six or more students stand shoulder to shoulder and you walk leisurely before them. Depending on the number of photo-shooters, each person can take maximum two photos (without using an app). Before the photo-shooting session, decide how you will trigger the event and how each member will know when they should start and finish taking their photos. The end result should be the same as in Task 1. Tell other groups how you accomplished the task.

Task

Date |

April 1878 | |

Place |

San Francisco | |

Task |

To take 12 consecutive photos of a galloping horse and place them end-in-end in order to produce the effect of a motion picture. See below for details. | |

Tools |

One of our cameras / Two of our photographers

|

|

Cameras |

12 | |

Photographers |

12 (if required) | |

Horse |

1 race horse | |

Rider |

1 jockey | |

Others |

Any other tool or material that might be necessary |

- You can do the experiment on a race track or on a field.

- It is vital that the horse is not harmed - race horses are expensive!

- In a group, make a detailed plan on your project. Take into consideration such points as:

- How many days do you need to complete the project?

- How much money do you expect to spend (remember that all the tools are free of charge)?

- How many tests will you need to do before the final photo-shooting session?

- Present your project to the whole class.

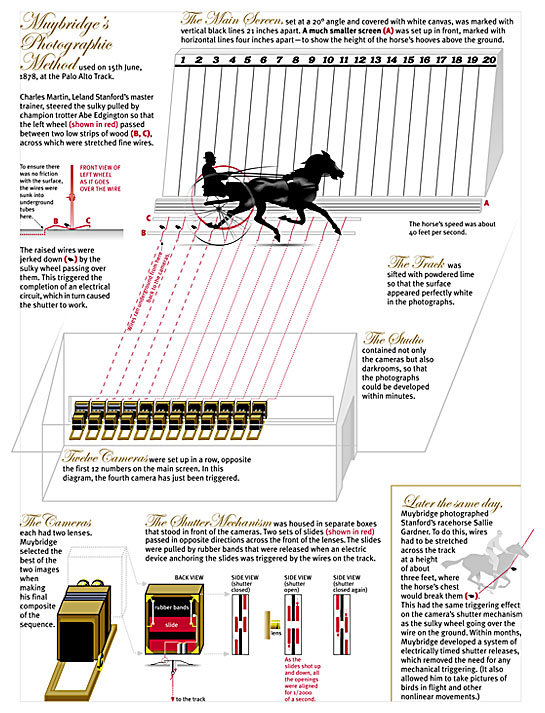

Muybridge's solution

The Man Who Stopped Time

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge stunned the world when he caught a horse in the act of flying.

By Mitchell Leslie

On a bright, balmy morning in June of 1878, a crowd of racing enthusiasts and newspapermen huddled beside the track on the Palo Alto Stock Farm, waiting to see a horse run. Leland Stanford had invited them to his estate and horse-training mecca to witness a photographic first.

The nation was swept up in a technological explosion. Americans swooned over inventions like the telephone and phonograph, while Edison prepared to unveil the lightbulb and Eastman set his sights on a handheld box camera. Having served his term as governor and launched a railroad empire, Leland Stanford was savoring life as a country gentleman.

Horses were his passion. For him, the racetrack demonstration would culminate five years of experiments, undertaken with photographer Eadweard Muybridge, to clinch a pet theory about equine gait. Is a running horse ever completely aloft? Stanford insisted the answer was yes.

Stanford and Muybridge opened the day's spectacle by showing off their meticulous preparations. On one side of the track stood a whitewashed shed, with an opening at waist level across the front. Peeking out were a dozen bulky cameras, lined up like cannons in a galleon. On the opposite side, a sloping white backdrop had been raised to maximize contrast. The show began as one of Stanford's prize trotters, driven by master trainer Charles Marvin, sped down the track pulling a two-wheeled cart called a sulky. Across the horse's path were 12 wires, each connected to a different camera. When a sulky wheel rolled over one of the wires, it completed an electrical circuit, tripping the shutter of the attached camera. The shutters firing in quick succession sounded like a drumroll.

A single exposure could take minutes in those days, but the state-of-the-art cameras managed all 12 shots in less than half a second. Within 20 minutes, Muybridge had developed the plates and laid out the results for the visitors to admire. The series made a brief filmstrip of the horse's progress along the track--capturing, for the first time, ephemeral details the eye couldn't pick out at such speeds, such as the position of the legs and the angle of the tail. Stanford got the evidence he wanted, and the world got a stunning dissection of motion. "It was a brilliant success," one reporter wrote. "Even the threadlike tip of Mr. Marvin's whip was plainly seen in each negative, and the horse was exactly pictured."

https://alumni.stanford.edu/get/page/magazine/article/?article_id=39117

You can find a very detailed graphic description on the next page.